HERO Structural Diagram" width="600" height="300" />

HERO Structural Diagram" width="600" height="300" />August 2021

Goal #1: Building a more resilient, flexible and integrated delivery system that reduces racial disparities, promotes health equity, and supports the delivery of social care

Goal #2: Developing Supportive Housing and Alternatives to Institutions for the Long-Term Care Population

Goal #3: Redesign and Strengthen Health and Behavioral Health System Capabilities to Provide Optimal Response to Future Pandemics & Natural Disasters

Goal #4: Creating Statewide Digital Health and Telehealth Infrastructure

Definitions

A widely used definition of health equity is the one developed and used by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF): “Health equity means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. This requires removing obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination, and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments, and health care.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines health disparities as: "preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or in opportunities to achieve optimal health experienced by socially disadvantaged racial, ethnic, and other population groups, and communities."

New York State (NYS or the State) requests $17 billion over five (5) years to fund a new 1115 Waiver Demonstration that addresses the inextricably linked health disparities and systemic health care delivery issues that have been both highlighted and intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic devastated many vulnerable populations of Medicaid recipients, with a particularly detrimental impact to populations with historical health disparities, including persons living in poverty, Black and Latino/Latinx and other underserved communities of color, older adult populations, criminal justice-involved populations, high-risk mothers and children, persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD), persons living with severe mental illnesses, persons with substance use disorders, and persons experiencing homelessness.

Understanding that health disparities differ by population, geography, and previous community investment, calls for a tailored approach based on these factors.

Addressing health equity and achieving an equitable recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, while advancing other long-standing delivery system reform goals of NYS, is a complex undertaking and requires a transformational, coordinated effort across all sectors of the health care delivery system and continuum of social services. Indeed, to address the full breadth of factors contributing to health disparities, NYS will not only pursue reforms and investment in the health care delivery system, but also in training, housing, job creation, and many other areas.

Accordingly, if approved, this waiver reflects that achieving an equitable recovery from COVID-19 is a process, not just an outcome, and would be just one part of NYS´s intertwined Reimagine, Rebuild, Renew initiatives that collectively form a unified statewide strategy for equitable COVID-19 recovery.

At the same time, because health and healthcare are local and the social service offerings may differ by region, this statewide strategy must also tie back to local gaps and needs, particularly for the health care safety net. Accordingly, NYS proposes an ambitious partnership with the Federal government through an 1115 Waiver Demonstration that creates a pathway to address and rectify these historic health disparities. This partnership is critical to addressing health disparities exacerbated by COVID-19, promoting health equity, and fulfilling the promise of the Medicaid program to provide comprehensive health benefits to those who need them.

If approved, this 1115 Waiver Demonstration would utilize an array of multi-faceted and linked initiatives in order to change the way the Medicaid program integrates and pays for social care and health care in NYS. It would also lay the groundwork for reducing long standing racial, disability-related and socioeconomic health disparities, increase health equity through measurable improvement of clinical quality and outcomes, and keep overall Medicaid program expenditures budget neutral to the federal government.

To achieve this overall goal of fully integrating social care and health care into the fabric of the NYS Medicaid program, while recognizing the complexity of addressing varying levels of social care needs impacting the Medicaid population, this waiver proposal is structured around four subsidiary goals:

Since the inception of New York´s 1115 waiver in 1997, New York has invested in and fortified one of the most comprehensive Medicaid programs in the country, and has frequently been among the first states to expand eligibility or incorporate enhanced benefits. The Medicaid program, combined with other state-supported health insurance options offered through the widely recognized NY State of Health Marketplace such as the Essential Plan and Child Health Plus, provides comprehensive coverage to nearly all low-income New Yorkers.

The comprehensiveness, value and accessibility of the Medicaid program has never been more important than during the COVID-19 pandemic. As the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is aware, the COVID-19 crisis hit New York first and hardest. The first confirmed COVID-19 case in New York occurred on March 1, 2020. Six weeks later, there were 18,825 COVID patients in New York hospitals. 1 At the peak of the pandemic, epidemiological models indicated that the State required inpatient capacity of anywhere from 55,000 to 136,000 beds for COVID-19 alone. 2 At the same time, public health authorities lacked extensive clinical and epidemiological knowledge about the treatment and spread of the disease, and health care workers faced rampant shortages of protective equipment. The State had to implement an emergency pause of the economy, enact immediate regulatory relief to facilitate care, and coordinate an operational response, all in real-time.

Responding to COVID-19 taught NYS critical lessons about coordinating an effective and massive response within the existing health care system, from ramping up the availability of testing to bringing hospital resources and staff to high-priority regions. During these efforts, losses in employer-sponsored coverage or changes in economic status resulted in the Medicaid program extending health coverage to more than 888,000 additional New Yorkers, growing from over six million enrollees in March 2020 to approximately seven million in March 2021.

Notwithstanding these successes in the mobilization of New York´s pandemic response and the ability of the State´s Medicaid program to absorb a tremendous influx of new enrollees, the pandemic revealed that even an immediate, effective emergency response was insufficient to overcome a long history of policies and practices in the U.S. that have contributed to inequity in health care and significant health disparities. This impact is reflected by the pandemic´s disproportionate impacts to low-wage workers and people of color, putting them at higher risk of getting sick and dying from COVID-19. 3 Additionally, as CMS is aware, Black and Latino/Latinx populations accounted for higher levels of COVID-19 related hospitalizations and mortality than white populations. 4 Critically, these studies have found that structural determinants and socioeconomic factors resulted in an increased likelihood of out-of-hospital deaths and infections than with other populations, and were a prime causal factor resulting in vastly higher mortality rates in these populations. 5 The higher rates of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths among people of color–due to their higher prevalence of chronic illness, overrepresentation in frontline and essential jobs, increased likelihood of living in multi- family or multi-generational housing, and other factors–have illustrated how pervasive health inequities remain.

Although the New York State Medicaid program has been actively working to improve health outcomes among Medicaid members, including through its groundbreaking and successful Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program, which began to develop and fund ways to address social determinants of health (SDH) and value-based payment (VBP), COVID-19 is evidence that significant health disparities persist. To that end, this waiver seeks to build on the prior work and the State´s learnings during COVID-19 in designing and evaluating practical, common-sense, and actionable ways to leverage New York´s robust Medicaid infrastructure to promote health equity for New Yorkers.

For the last decade, through its current 1115 waiver, NYS has engaged in efforts to redesign Medicaid using managed care and its recently ended DSRIP program. DSRIP had an overall goal of reducing avoidable hospitalizations by 25 percent and achieving savings while transforming the health system to use VBP. NYS achieved many of its goals with DSRIP, including a 26 percent reduction in Potentially Preventable Admissions (PPAs) and an 18 percent reduction in Potentially Preventable Readmissions (PPRs) through Measurement Year 5; facilitated a significant increase in Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) certification; made major progress in integrating physical and behavioral health care; and improved care transitions that directly reduced readmissions. The DSRIP program also incorporated a Value-Based Payment Roadmap, which achieved its goals of at least 80% of the value of all Medicaid managed care contracts in shared savings (Level 1) or higher VBP arrangements, and 35% of contract value in upside and downside risk (Levels 2 and 3) arrangements. As a result of all these initiatives and others in the State´s current 1115 waiver, as well as other Medicaid redesign initiatives, NYS Medicaid spending per beneficiary in 2019 was less than in 2011.

With this waiver demonstration proposal, NYS is incorporating lessons learned from its DSRIP experience, including the need for regional alignment on objectives, more direct investment in and involvement of CBOs and behavioral health providers in governance and VBP accountability, regional coordination of workforce initiatives to address shortage areas, administrative simplification through avoiding the creation of new intermediary entities, and an even deeper alignment of provider and payer incentives–particularly the highest level of VBP, with symmetrical risk sharing and monthly prepayments (capitation and/or global budgets). The current demonstration waiver request is intended to further advance the combination of the State´s previous DSRIP goals with the more explicit prioritization of integrating social care and health care into the NYS Medicaid program in order to increase health equity across the needs of New York´s vulnerable and underserved populations that were revealed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Building on the promise of DSRIP, the integration of social care through meaningful reward incentives and member risk adjustment will be the vehicle through which NYS can achieve and sustain the benefits of this demonstration.

To achieve the four goals identified above and support the integration of social and health care into the NYS Medicaid program, this waiver demonstration proposes upfront direct investments in the following areas:

As described above, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted and, in some cases, exacerbated the impact of long-standing health disparities based on race, ethnicity, disability, age, and socioeconomic status. Specifically, the COVID-19 pandemic and its higher rates of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths among people of color and other minority populations and people with disabilities due, their higher burdens of disease, over representation in low-wage essential jobs, increased likelihood of living in multi-family or multi-generational housing or institutions, and other factors demonstrated how pervasive health inequities are in NYS. 6 Additionally, based upon existing measurement sets and data collection efforts, including the biennial New York State Health Equity Report, the quality of and access to health care services in low-income communities and among racially and ethnically diverse population groups reflects a health care delivery system that is not designed to meet community needs and eradicate health disparities. 7

These findings are a reflection of a health care delivery system that has been historically structured to address illness and disease-burden with patients presenting in hospitals or clinics when care is needed. Through the DSRIP experience, NYS´s provider community and managed care organizations (MCOs) have learned new, more efficient ways to address individual and population health. In turn, these efforts have begun to create the collective recognition that theability of MCOs and providers to coordinate effectively to address SDH directly influence how and if Medicaid members remain stable and healthy in community settings. Moreover, these interventions have the demonstrated potential to improve their health outcomes and prevent disease, which has only revealed the further limitations of delivery systems that are built for "sick care."

It is now widely acknowledged that SDH factors, rather than medical interventions and services, are the key driver for a large majority–up to 80 percent–of health outcomes. 8 Moreover, SDHs are often the direct reason for health inequities, such as differential rates of diabetes related to lack of access to healthy food. Nationally, there are an increasing number of successful attempts to scale proven SDH interventions; however, NYS believes that these interventions can scale further–from helping thousands to helping millions. The State believes CMS shares this vision, as demonstrated through its increasing willingness to use 1115 waiver authority to permit state Medicaid programs to address SDH interventions and funding gaps. For example, CMS approved North Carolina´s 1115 waiver in 2019, which seeks to use Medicaid to pay directly for some non-medical inventions targeting housing, food, transportation, and interpersonal violence/toxic stress supports. 9

Building on these efforts, NYS recognizes that, in order to further our collective ability to improve health outcomes for all patients, particularly those who are vulnerable and underserved, the State must augment existing systems and develop a nimble delivery system built for "well care," that includes the following features:

This waiver proposal is a catalyst to developing this new delivery system, and will require thoughtful planning, coordination and execution to address and reduce health disparities, while minimizing disruption and limiting unintended consequences. Furthermore, NYS recognizes that any success will reflect the regional differences and needs of our diverse state, as populations may be impacted differently and experience varying levels and types of health disparities and social care needs.

Past waiver experiences have shown how targeted investments in effective regional coordination can create stakeholder alignment around aggressive actions to implement policies and programs that achieve delivery system reform. These same strategies can be equally successful in addressing racial, ethnic, disability, age, and socioeconomic disparities in care, promoting a common framework for assessing and measuring improvements in health equity, and strengthening the entire NYS health care delivery system. The disparate impact of COVID-19 on disadvantaged populations demands a comprehensive response that addresses underlying SDH as an inherent part of addressing health disparities and achieving health equity. Building on longstanding investments and efforts, the Medicaid program is in an excellent position to bridge this gap based on the demographic composition and physical health, behavioral health and social needs of its beneficiaries. Although New York´s DSRIP program included some projects addressing SDH, these early attempts need to be brought to scale across the state. NYS has learned from this experience and believes that a more structured approach, as highlighted below, will more successfully connect traditional health care services and SDH service systems, in order to take a more holistic approach to health care and address the health needs of the whole person.

To reinforce these efforts and address sustainability, NYS will integrate health equity as a fundamental standard for the investments in advanced VBP arrangements, providing support through the development of SDH networks of care and Health Equity Regional Organizations (HEROs). This approach will also allow for targeted new investments in social care and non- medical, community-based services that directly address SDH, as more fully described below.

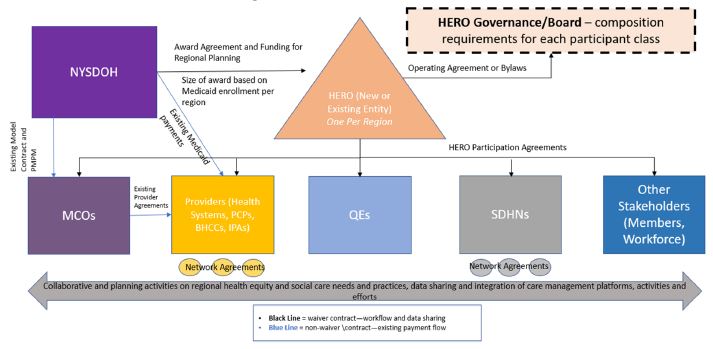

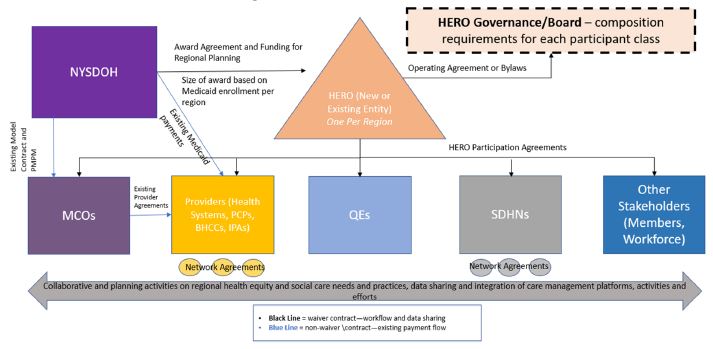

This demonstration will pursue the development of HEROs, which will be mission-based organizations that build a coalition of MCOs, hospitals and health systems, community-based providers (including primary care providers), population health vehicles such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and independent provider associations (IPAs), behavioral health networks, providers of long-term services and supports (LTSS) including those who serve individuals with I/DD, community-based organizations (CBOs) organized through social determinants of health networks (SDHNs, as described below), Qualified Entities (QEs) (which in New York are Health Information Exchanges (HIEs) and Regional Health Information Organizations (RHIOs)), consumer representatives, and other stakeholders (See Exhibit 1). They will be regionally focused in order to align with the health equity needs that differ by community and future value- based payment contracting structures.

HERO Structural Diagram" width="600" height="300" />

HERO Structural Diagram" width="600" height="300" />

HEROS may be led by a variety of existing and new corporate entities (e.g., LLC, not-for-profit) including but not limited to local departments of health or social services, behavioral health IPAs and other structures formed by regional participants. Similar to the Accountable Health Communities model in states such as Hawaii, or Washington´s Accountable Communities of Health bodies, HEROs would focus on collaboration and coordination, and facilitation of activities that best address the needs of the communities they serve (with the goal of raising the overall health of these communities).The HEROs would not receive and distribute waiver funds similar to intermediary entities in other waiver demonstrations approved by CMS. Rather, the HEROs would receive limited planning grants under the waiver, be able to receive and ingest data from national, State, local and proprietary data sources, and assume a necessary regional planning focus in order to create collaborations, draw insights from different data sources and needs, and develop a range of VBP models or other targeted interventions suitable for the populations and needs of each region that would be funded through the mechanisms described in Section 1.3 below.

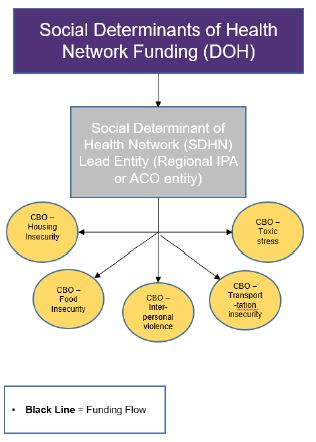

Differences in SDH factors are a primary contributor to racial and disability disparities in health outcomes. A growing number of innovative CBOs are employing interventions in SDH areas, such as community health worker support, healthy behaviors, nutrition, social isolation, education, transportation, and the organization of benefits and employment. While planning and coordination needs will be addressed by HEROs, there is an urgent need to organize CBOs and social service providers and develop the programming and workflows necessary for them to coordinate and work with health care delivery systems. NYS will catalyze this process through a separate investment in coordinated networks of CBOs–referred to as Social Determinant of Health Networks (SDHNs)–that take a comprehensive and outcomes-focused approach to addressing the full spectrum of social care needs offered by CBOs in a region, create a supportive IT and business processes infrastructure, and adopt interoperable standards for a social care data exchange. Critically, this type of CBO network development began to catalyze as a logical outgrowth of DSRIP, with several Performing Provider Systems (PPS) or providers within a PPS, electing to form network entities that are capable of participating meaningfully in VBP arrangements. Examples of these developing SDHNs include the Healthy Alliance Independent Practice Association (IPA), which described itself as "the first IPA in the nation entirely devoted to addressing social determinants of health;" 15 the EngageWell IPA, which "was created by New York City not-for-profit organizations working together to offer coordinated, integrated treatment options that include addressing social determinants of health–housing, nutrition, economic security;" 16 and SOMOS Innovation "a full implementation of the holistic care model" and "the next step on the path to culturally competent Value-Based [H]ealthcare." 17

Each lead entity would create a network of CBOs that will collectively use evidence-based interventions to coordinate and deliver services to address a range of SDH needs that will improve health outcomes, including housing instability, food insecurity, transportation, interpersonal safety, and toxic stress. The SDHN in each region would be responsible for: 1) formally organizing CBOs to perform SDH interventions; 2) coordinating a regional referral network with multiple CBOs, health systems and other health care providers; 3) creating a single point of contracting for SDH arrangements; and 4) screening Medicaid enrollees for the key SDH social care issues and make appropriate referrals based on need. The SDHNs can also provide support to CBOs around adopting and utilizing technology, service delivery integration, creating and adapting workflows, and other business practices, including billing and payment. These SDHNs will coordinate and work with providers in MCO networks to more holistically serve Medicaid patients, particularly those from marginalized communities, effectively wrapping a social services provider network with existing MCO clinical provider networks.

As evidenced by Exhibit 2, SDHNs will receive direct investments to develop the infrastructure necessary to support this network of care, including to develop the IT and business processes and other capabilities necessary. CBOs in these networks will also receive funding necessary to integrate into this network and provide services.

Exhibit 2: SDHN Structural and Funding Diagram

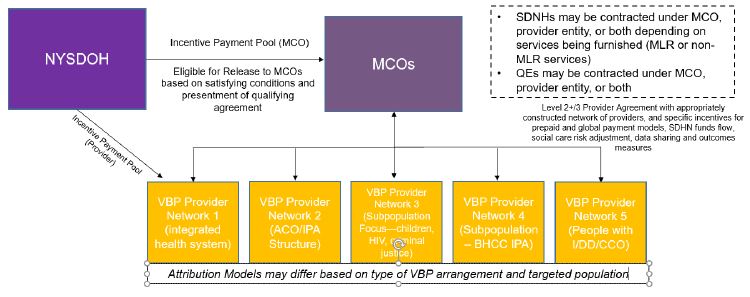

With the HERO and SDHN infrastructure established, advanced VBP arrangements will support the mid- to long-term transformation and integration of the entire NYS health care and social care delivery system by funding the services needed to address SDH at scale. Under this structure, incentive awards would be made available to MCOs (that have participated meaningfully in HEROs) providers and organizations in qualifying VBP contracts approved by DOH. MCOs would be required to engage in VBP contracts with an appropriately constructed network of providers for the population-specific VBP arrangement. For example, behavioral health IPAs and/or other behavioral health provider networks would be included along with primary care providers for VBP arrangements targeting the SMI, SUD, and dually diagnosed populations. In these instances, DOH would award the pertinent waiver funding based on differential attribution methodologies utilizing a member´s primary behavioral health provider (e.g., Article 31 clinic) or Health Home focusing on individuals with behavioral health diagnoses, rather than a primary care only attribution methodology. Similarly, for VBP arrangements involving people with I/DD, attribution may occur based on the individual´s Care Coordination Organization (CCO).

The VBP funds through this waiver proposal would encourage the evolution of the MCO- network entity agreements into more sophisticated VBP contracting arrangements that incorporate health equity design, fund the integration with social care, adjust risk to reflect both the health care and social care needs of their members, reward providers´ improvements in traditional health outcome measures as well as advanced or stratified health equity measures informed by the HERO, and/or use fully prepaid payment models that fortify against fluctuations in utilization based on pandemics. In particular, using socially risk adjusted payment–whether through accurate use of z-codes or the data collected from the uniform social care assessment tool described above–can incentivize and appropriately reward plans and providers for caring more holistically for these vulnerable populations. 19 Prepayment approaches would also be available to providers who are not the lead VBP contractor but are providing care to the lead contractor´s attributed members through a downstream targeted or bundled arrangement.

The State recognizes that there have been successes under DSRIP, especially with VBP readiness and transition, that should continue under this new waiver demonstration. PPSs that have shown deep experience and success with New York´s current VBP arrangements, including through designation as "Innovators" under current, CMS- approved version of A Path toward Value-Based Payment: New York State Roadmap for Medicaid Payment Reform (VBP Roadmap), 20 with the necessary infrastructure and experience serving their communities and specific populations, may be eligible for upfront VBP incentive funding to facilitate the transition to these new health equity- driven VBP arrangements.

Additionally, this component of the waiver would seek specific authorities for NYS to utilize global prepayment payment models in selected regions where these arrangements logically apply; that is, where there is a lead or dominant health system or financially integrated provider-based organizations with demonstrated ability to manage the care of targeted populations in that region. In a global model, the lead health system VBP entity–whether part of an integrated delivery system or clinically and financially integrated IPA or ACO–would extend successes and performance across payor types, including Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS), Medicaid managed care, Medicare FFS, Medicare Advantage, and/or commercial plans.

Exhibit 3: VBP Incentive Structural Diagram

Workforce and training are critical foundations to achieving the health equity goals under this proposal and to developing delivery systems of "well care" capable of serving the whole-person. To provide the SDH interventions through the SDHNs, NYS will need to expand the number of community health workers, care navigators and peer support workers, particularly drawing from low-income and underserved communities to ensure the workforce reflects the community they serve. Workforce training will also support regional collaboration under the HEROs, the SDHNs, and the move to advanced VBP models, including:

This waiver component also expands workforce investments, including creating additional career pathways for these community health occupations so that entry level workers such as home health aides and dietary aides with strong community ties can advance in their career, and expanding on current apprenticeship programs and cohort training programs for community health occupations. These programs will provide opportunities to increase the economic mobility of individuals in the community, which in turn, plays a role in achieving health equity through addressing economic stability and job creation.

Based on historical data in New York, approximately 83 percent of incarcerated individuals are in need of substance use disorder treatment upon release, according to the New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (DOCCS). 23 Meanwhile, the share of individuals in New York City´s jails who have mental illnesses has reached nearly 40 percent in recent years, even as the total number of incarcerated individuals has decreased. 24 Incarcerated individuals with serious health and behavioral conditions use costly Medicaid services, such as inpatient hospital stays, psychiatric admissions, and emergency department visits for drug overdoses at a high rate in the weeks and months immediately after release. Even under the best of circumstances, when a person is discharged without prior contact with a future care manager/provider or without long-acting depot medications or other addiction/mental health medications as indicated, there is a high likelihood they will not engage with critical service providers when they re-enter the community. Contact between service providers and the incarcerated individual needs to occur prior to release to facilitate the continuity of care after discharge and the use of medications appropriate for community-based (rather than jail or prison) settings.

To achieve its health equity goals, NYS recognizes this is a particularly vulnerable population, especially individuals with co-occurring conditions, who must maintain connectivity and access to critical services and medications as they transition back to community settings. NYS has identified that expanding Medicaid eligibility for the criminal justice-involved population is critical to achieving the waiver´s health equity goals; therefore, the State is seeking to build and strengthen the relationship between the care provided inside its jails and prisons and the care offered by Medicaid providers upon release, ensuring appropriate transition and supports during re-entry to ensure particularly vulnerable patients with comorbidities have the housing and other supports they need to stabilize in a community setting. This population can then be more effectively served as part of the health equity-informed VBP arrangements described above. With this purpose in mind, NYS seeks approval for the following eligibility changes:

Taken together, this series of investments would enable a statewide strategy to address SDH at scale, while maintaining the flexibility to direct resources based on specific local challenges and needs, tied to health equity goals. The components of this overall framework are firmly rooted in the recommendations from the National Quality Forum in how states should promote health equity and eliminate health disparities:

Transitioning individuals to community-based settings from institutional care and connecting people to stable housing have long been priorities of New York State, and the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this concern. During the pandemic, individuals and families experiencing homelessness are at significant risk of infection in congregate settings, such as homeless shelters, and may have also lost access to other supports, such as services and food provided through schools. Individuals experiencing homelessness are also more likely to have underlying conditions, behavioral health issues, substance use disorders, and limited access to health services. Individuals who reside in long-term care institutions (such as psychiatric facilities, nursing homes, congregate care facilities, and Intermediate Care Facilities for people with I/DD) and correctional facilities were also disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, experiencing increased rates of infection and the disruption of necessary habilitative or rehabilitative services. The housing needs of these individuals are likely to be ongoing and escalate as the public health emergency order is lifted and the end of eviction moratoria results in greater housing instability and homelessness. Given this experience and ongoing need, NYS proposes to build on its existing and innovative work in supportive housing and community integration.

Building on NYS Supporting Housing Programs: Supportive housing was a major initiative of the Medicaid Redesign Team (MRT) in 2011. Since that time, the MRT has made significant financial commitments for rental subsidies and supportive housing services. In addition, New York State committed to a $20 billion, five-year capital plan in 2017 to build or preserve more than 100,000 affordable and 6,000 supportive housing units, and also funds supportive housing programs directed at specific populations, including individuals with I/DD or physical disabilities, those individuals with serious behavioral health needs and addiction needs, and older adults.

The MRT supportive housing initiative is composed of a diverse set of programs that target high utilizers of Medicaid and use a variety of approaches to provide housing and supportive services to different populations statewide, with a heightened focus on New York City. These programs include 54 capital projects, 13 rental subsidy and supportive services programs and pilots, and one accessibility modification program. The programs serve homeless individuals with HIV/AIDS, serious mental illness, I/DD and other developmental disabilities, or chronic conditions. The initiative also targets those individuals who are living in institutional settings who can safely live in community-based settings.

The MRT supportive housing initiative has undergone a rigorous 5-year evaluation. Overall, the initiative has shown a reduction in the number of emergency department visits and inpatient hospital stays. On average, Medicaid claim costs declined by about $6,800 per person with high utilizers of the programs having an average savings of $45,600. Programs that transitioned individuals from nursing home settings saved an average of $67,255 the first year and $90,239 the second year in housing. 27

Continued Demand for Supportive Housing Programs Exacerbated by the COVID-19 Pandemic: During and outside of the pandemic, access to transitional and permanent housing and supports are indispensable aspects of a viable safety net and of health equity, as demonstrated by the success of the MRT investments and NYS´s experience during the pandemic. People who are homeless with complex medical problems are one of the highest cost groups of individuals enrolled in New York Medicaid, driving a large portion of avoidable hospital costs through lack of access to care outside the emergency department. They are disproportionately affected by behavioral health conditions, including substance use disorder. Housing investments, if supported by innovative services and VBP, can produce a great return on investment.

NYS seeks to extend this effort through additional supportive housing programming, which the State expects will be necessary to address downstream effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as additional instability in housing for many Medicaid-eligible individuals and families and an urgent need for supportive housing for people experiencing homelessness. NYS seeks the following investments to support Medicaid patients who are particularly vulnerable due to the lack of or unstable housing:

HEROs would then work on identifying housing solutions for the areas and populations where gaps exist, coordinating between MCOs, SDHNs and local government entities overseeing local housing programs. Funds would be available for these entities to undertake this assessment and planning effort. The regional HEROs would also engage in planning efforts in order to develop alternatives to remain in community-based settings.

There are several subpopulations with co-occurring conditions exacerbated by the lack of housing or unstable housing. To ensure that individuals with serious mental illness and substance use disorder receive needed housing and stability as they transition from institutions and residential services, NYS will seek approval to:

These investments, in its totality, would ensure benefit continuity and support for individuals transitioning to community living whose at-risk due to unstable or lack of housing.

Although this waiver demonstration´s primary focus is to address disparities in access to quality health care and social care and achieve an equitable pandemic recovery, the COVID-19 pandemic also revealed that NYS must have a ready-to-execute strategy to respond to a significant increase in demand for acute care services. This includes a greater volume of hospitalizations, higher intensity of care services, and the need to replace disrupted acute and chronic healthcare services that are attributable to a pandemic. Redesigning the healthcare delivery system to efficiently achieve better outcomes in underserved areas during non- emergency times must be done in a manner that also supports rapid mobilization of resources for pandemic response demands on hospital capacity, workforce, supplies and continuation of essential healthcare services and quality care during an ongoing crisis. While it is critical for this redesign process to ensure the necessary flexibility in the hospital system for a coordinated and sufficient increase in staffed operating beds above what is needed in non-emergent times, it is equally important that such design provides a model that optimizes the role of every healthcare resource to create the proper balance between efficiency and redundancy to support a pandemic response. These initiatives include:

A silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the opportunity for–and accelerated realization of–widespread consumer and provider use of digital and telehealth care, including tools such as remote patient monitoring, innovative care management technologies, and predictive analytics. Consumers report high satisfaction with telehealth options, with prominent surveys showing satisfaction levels of 86-97%, often higher than for in-person visits. 29 Preliminary data also suggests that telehealth has been a critical means at reaching hard-to- engage populations with historical access issues, especially for behavioral health services. 30 With the State´s continued push towards advanced VBP models, digital tools and telehealth will be critical means by which the health care system can adjust the mechanisms for care delivery to become more focused on outcomes than billable events, with flexibility in the frequency and duration of virtual visits and other digital modalities of care. Telehealth can also increase access to high-demand specialties, and improve use of tools such as home monitoring to anticipate and prevent acute events by extending the eyes and ears of providers into home and community settings.

Through an 1115 demonstration, NYS can ensure that this consumer-driven wave is available equitably by building digital and telehealth infrastructure and care models to significantly expand access to care, both in underserved areas, such as rural and other communities without convenient access to primary or specialty care, and for underserved needs, such as behavioral health and the management of chronic diseases. NYS will promote the elimination of health disparities, in part, by ensuring equitable use and availability of telehealth, including telephonic- only service delivery, across communities of color and other marginalized areas. Digital health and telehealth capabilities for safety net providers need to expand beyond simple, siloed solutions thrown into service during an emergency into thoughtfully designed platforms integrated with EHRs, care management programs, social care services, the statewide health information exchange, and professionals and non-professionals trained to maximize the use of such technology.

Reimbursement levels in Medicaid populations served by safety net providers are not sufficient to make these investments on their own, as they sometimes are in the commercial market. The State will therefore use waiver funding to create an Equitable Virtual Care Access Fund to assist such providers with these human capital investments, resources, and support. Greater use of telehealth, virtual care and other digital health tools has many other potential benefits, including expanded access to specialists and better use of statewide system capacity, improved ability to engage in follow-up care, better ability to care for patients in a comfortable home setting, and improved convenience. Studies have shown significantly reduced rates of cancelled appointments when telehealth was utilized, compared to in-person visits only. 31 In approving plans and distributing funds for flexibility in health system capacity, the State will take into consideration appropriate payment mechanisms to promote virtual encounters to improve services to vulnerable populations and to address ongoing workflow disruptions and/or staffing shifts due to the COVID-19 emergency.

Significant additional planning and investment is critical to create a robust infrastructure for telehealth, telephonic, virtual and digital healthcare. Through a statewide collaborative group, the State will identify local strategies/solutions for mutual assistance and to also inform statewide standardization of technical requirements, workflows, as well as training and technical assistance to further build the necessary infrastructure to meet the immediate and long-term needs.

On an ongoing basis, the State may choose to engage in other population health activities that are supported by virtual care, including:

Funding and technical assistance through the Equitable Virtual Care Access Fund will bolster the ability of safety net providers to provide telehealth through various modalities. These may include:

Each of these goals and their associated initiatives and investments address key challenges identified during the pandemic, as well as health disparities and racial inequities that hamper the State, MCOs and providers to collectively meet the needs of some of the most at-risk and underserved populations within our Medicaid population. Taken together, these initiatives create synergies that reinforce and support the overarching goals of this waiver proposal and our collective ability to stabilize and better serve all of our Medicaid population, particularly those most impacted due to longstanding racial and health disparities.

Strengthening the safety net is a top priority for the State, but NYS´s own fiscal position has been undermined by the pandemic and it could not afford such funding on its own. In fact, absent federal support in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA), the State would have been forced to reduce safety net expenditures immediately, as originally proposed in the State Fiscal Year 2021-22 Executive Budget. As required for a 1115 waiver, New York will meet budget neutrality requirements, post rebasing, but seeks additional flexibilities to support this proposal.

In addition to financing the non-federal share of this 1115 demonstration through transfers from units of local government and state general revenue commitments that are compliant with section 1903(w) of the Social Security Act, New York seeks flexibility from CMS to identify other sources of matching funding. Specifically, given the focus of this larger demonstration on the long-term effects of COVID-19, it would be appropriate to recognize that local governments, public benefit hospitals, and the State have been required to make substantial commitments of capital and resources to combat COVID-19 prior to availability of any federal funding through the Family First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA), the CARES Act, ARPA, or other sources of federal funding that will be made available to states that are experiencing the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

To the extent CMS and the State are able to identify state and local financial commitments, similar to the State Designated Health Programs that have been used to fund health care services and have replaced traditional Medicaid-covered services or programmatic administrative activities, NYS asks to revisit prior administrative guidance issued by CMS and allow these expenditures to be counted towards New York´s non-federal share under this 1115 waiver. NYS and CMS could also work to identify federal savings that would accrue outside the Medicaid program, such as savings to the Medicare program due to reduced spending on the dual eligible population.

1. New York Forward, Daily Hospitalization Summary by Region, available here. 1

2. Governor Cuomo, Amid Ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic, Governor Cuomo Announces Five New COVID-19 Testing Facilities in Minority Communities Downstate Press Briefing Transcript, April 9, 2020, available here. 2

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups, Updated April 19, 2021 and available here. 3

4. Gbenga Ogedegbe, M.D. et al., Assessment of Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Hospitalization and Mortality in Patients with COVID in New York City, JAMA (Dec. 4, 2020). 4

5. Benjamin D. Renelus et al., Racial Disparities in COVID-19 Hospitalization and In-Hospital Mortality at the Height of the New York City Pandemic, J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (Sep. 18, 2020). 5

6. United Hospital Foundation, New York State Medicaid Health Equity Options, at 1 (March 2021). 6

7. NYS Department of Health, New York State Health Equity Report (April 2019), available here. 7

8. Moody´s Analytics, Understanding Health Conditions Across the U.S. BlueCross BlueShield Association. December 2017, available here. 8

9. North Carolina´s Medicaid Reform Demonstration, approved October 19, 2018, see Attachment G a, available here. 9

10. Similar to Rush University Medical Center´s (RUMC) Anchor Mission Strategy. See Ubhayakar S, Capeless M, Owens R, Snorrason K, Zuckerman D., Anchor Mission Playbook, Rush University Medical Center and The Democracy Collaborative; August 2017, available here. 10

11. The NYS Department of Health Office of Health Insurance Programs has found through its research and assessment of screening tools that the AHC social needs screening tool may be an appropriate tool to use statewide. NYS DOH OHIP, Social Determinants of Health Standardization Guidance (April 2020). 11

12. National Committee for Quality Assurance, Distinction in Multicultural Health Care, available here. 12

13. CMS, New York Geographic Rating Areas: Including State Specific Geographic Divisions, available here. 13

14. Common Ground Health, About Us, available here. 14

15. Alliance for Better Health, Healthy Alliance Independent Practice Association, Innovative Health Alliance of New York, and Fidelis Care Join Forces to Improve Health by Addressing Social Determinants of Health CISION PR Newswire, (Sept. 23, 2019), available here. 15

16. EngageWell IPA, About Us, available here (accessed on July 6, 2021). 16

17. SOMOS, About SOMOS Innovation, available here (accessed on July 12, 2021). 17

18. The Commonwealth Fund, Review of Evidence for Health-Related Social Needs Interventions, July 2019, available here; Pruitt, Z et al. Expenditure Reductions Associated with a Social Service Referral Program, Population Health Management, Vol. 21, No. 6, Nov. 28, 2018, available here. 18

19. Jaffrey, J. and Safran, D., Addressing Social Risk Factors in Value-Based Payment: Adjusting Payment Not Performance to Optimize Outcomes and Fairness, Health Affairs, April 19, 2021, available here. National Quality Forum, A Roadmap for Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities: the Four I´s for Health Equity, September 2017, available here. 19

20. The VBP Innovator Program provided special designation for experienced VBP contractors as a mechanism to allow experienced providers to continue to chart their path into VBP. The Innovator Program is a voluntary program for VBP contractors prepared for participation in Level 2 (full risk or near full risk) and Level 3 value-based arrangements. These providers enter into Total Care for General Population and/or Subpopulation arrangements and are eligible for up to 95% of the total dollars that have been traditionally paid from the State to the MCO. NYS DOH, VBP Roadmap 56 (September 2019), available here. 20

21. See VBP Roadmap, at 4. 21

22. K.S. Chen, T. Robertson, M. Wu, et al., The Impact of the PCMH Model on Poststroke Follow-up Visits and Hospital Readmissions, Health Services Research, 2020. 22

23. Identified Substance Abuse, State of New York Department of Correctional Services (Dec. 2007). 23

24. City of New York, Mayor´s Task Force on Behavioral Health and the Criminal Justice System: Action Plan (Dec. 2014), available here. 24

25. Wachino, V. and Artiga, S., How Connecting Justice-Involved Individuals to Medicaid Can Help Address the Opioid Epidemic, Kaiser Family Foundation (June 17, 2019), available here. 25

26. National Quality Forum, A Roadmap for Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities: the Four I´s for Health Equity (September 2017), available here. 26

27. MRT Supportive Housing Evaluation Report, forthcoming. 27

29. Ramaswamy, A, Yu, M., et al. Patient Satisfaction with Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Retrospective Cohort Study, Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020; 22(9) and J.D. Power, 2020 U.S. Telehealth Satisfaction Study, October 2020. 29

30. Lau, J., Knudsen, J., et al. Staying Connected in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Telehealth at the Largest Safety-Net System in the United States, Health Affairs, June 11, 2020, available here.30

31. S. Jeganathan, L. Prassannan, et al. Adherence and acceptability of telehealth appointments for high-risk obstetrical patients during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, September 22, 2020, available here.31